The Key. Book Interview With Caleah

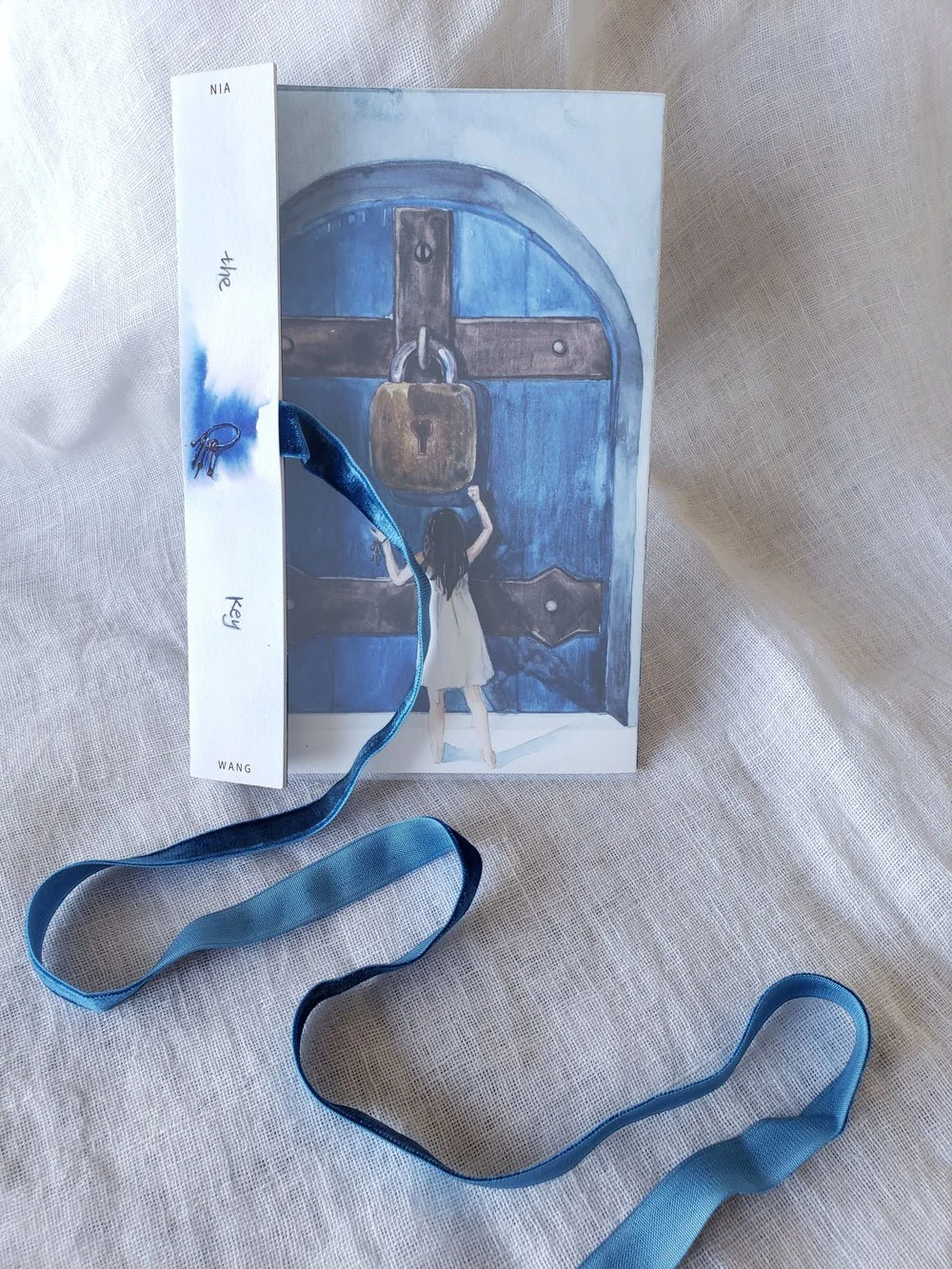

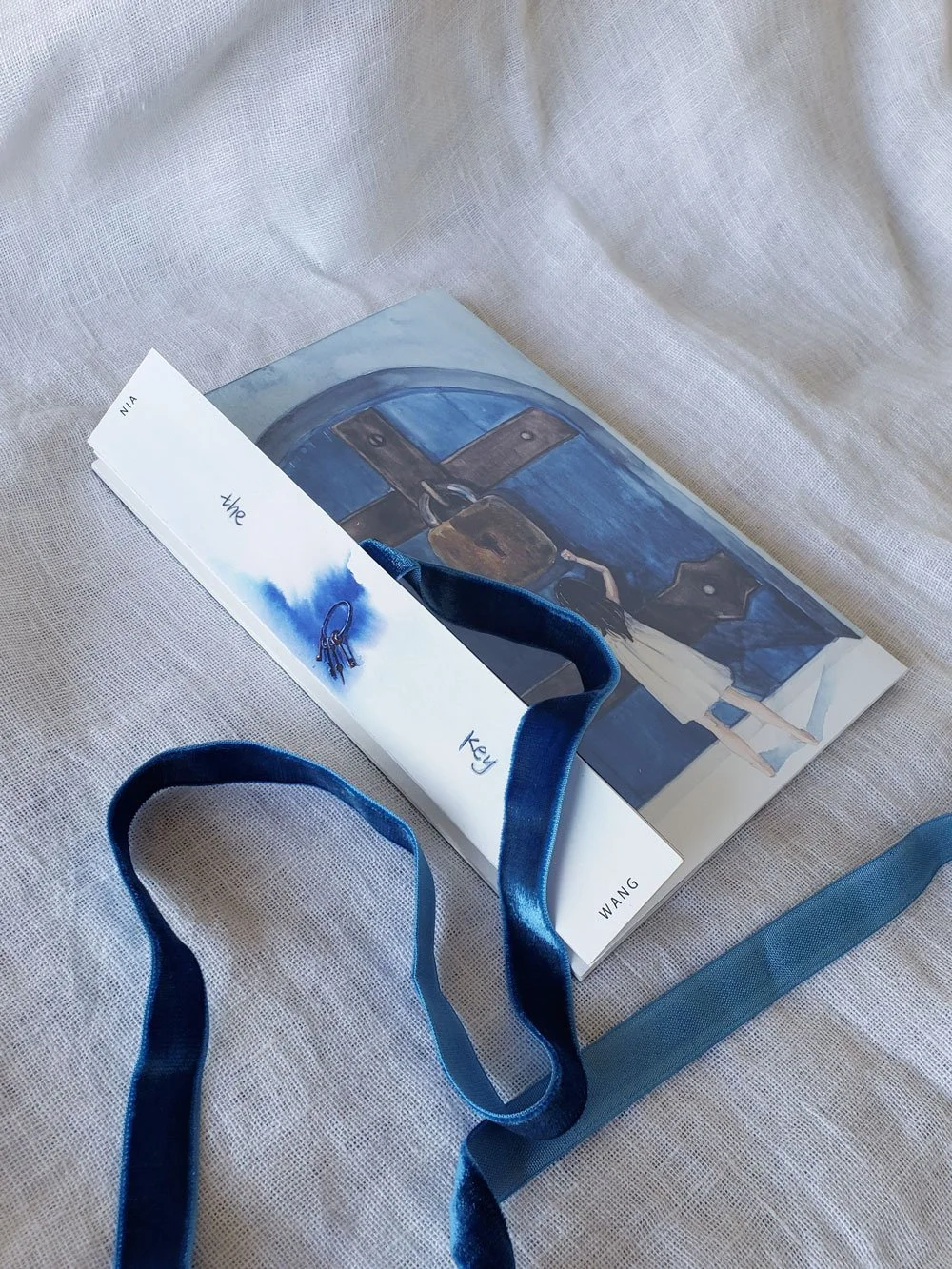

Diva Espresso on Greenwood Ave looks like a little brown house, with small windows and dark wooden siding. The inside, however, opens unexpectedly into a bright, open, white-walled space filled with warm coffee smells. Nia and I sat at a window table—observed by a regal, pearl-decked peahen looking down her beak at us from her gilt frame—to discuss the book that I was most eager to see again after the glimpse she gave me at our last meeting: The Key. This little blue book, with its unconventional cover and blue satin ribbon, dropped an unexpected emotional stone into my stomach the first time I flipped through it. I had felt as if I were looking at a physical manifestation of my own inexpressible emotion and I was eager to see if that experience would be repeated on my second look. I was not disappointed.

When did you paint these pieces?

I did these paintings about 10 years ago as two spreads that became part of my first art show in the United States. And then I made The Key [the book] last year.

Did you have any idea that it would become a book when you were painting the panels?

No, not when I first painted them, but it was always a story and I’ve always wanted to make tangible books—I love the process of choosing paper, the binding, the format, and a lot of my work just makes the most sense to me in that dimension. Last year I went on a bookmaking spree; I looked around at all my paintings and decided, since many of them already told stories, that I would make those into books.

How did you choose the design for The Key?

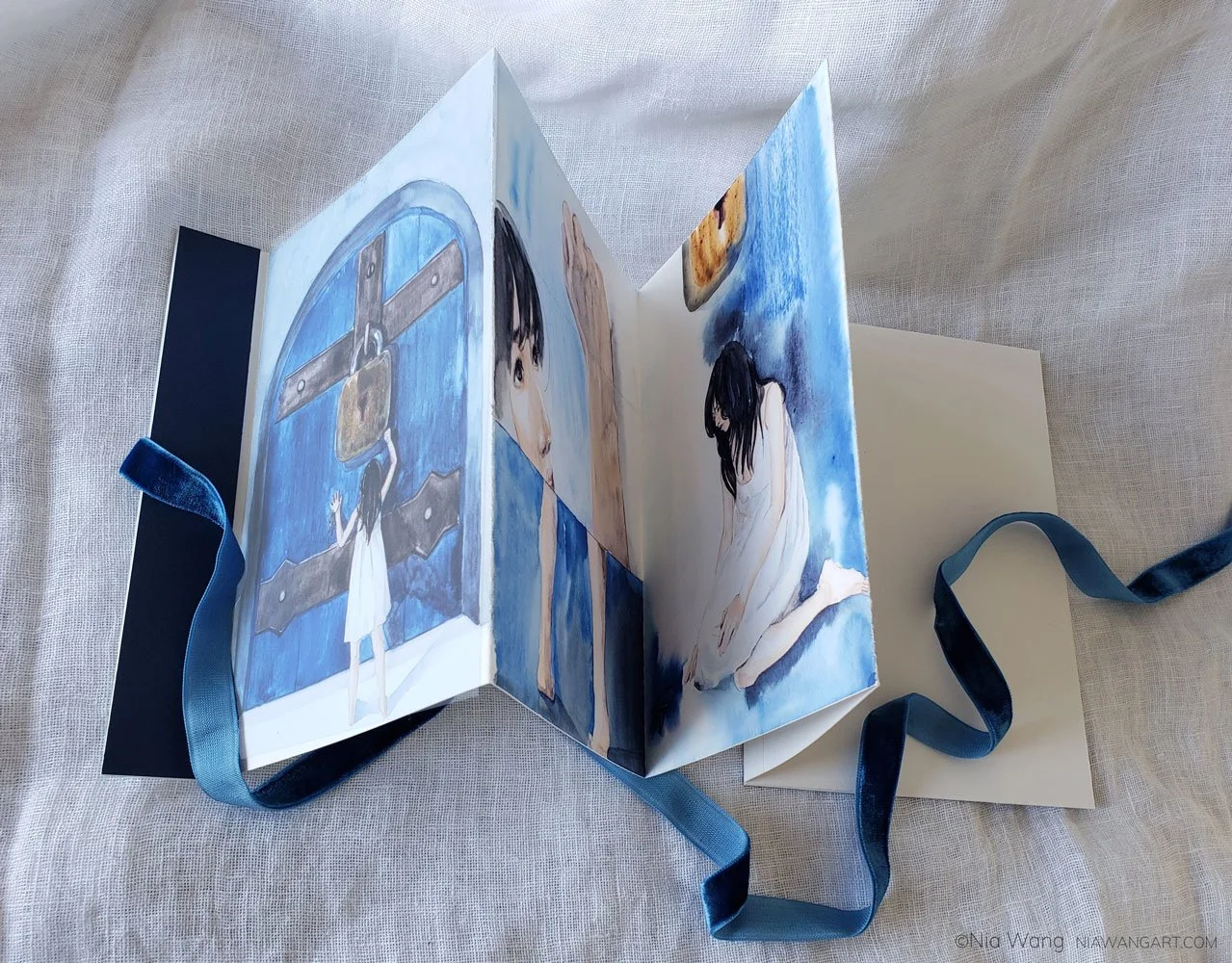

I considered making a cover out of the same material as the back and having the reveal when you open the book, but I decided that this form, using the title flap, the ribbon, and a loose-leaf of vellum as the “cover,” created more anticipation. The first thing you see is the first line of the story, so to speak: There’s a woman reaching up on tiptoe to knock on a door, but you don’t know where it leads or if she’ll be allowed in. That’s my style generally, I think. I like to create suspense. To make each page not necessarily make sense on its own, but to draw you on so that the next page can illuminate the one before, and by the end, you understand the complete story. I think giving a sneak peek creates more excitement.

In one of our previous conversations, you talked about being inspired by moments in your life. Was this story inspired by any particular event or moment, or was it an emotion or feeling you felt?

No, there was no specific event, it was just a feeling: the realization of loss. I’ve been taking a deep dive into the emotions of romantic love in a few of my recent and ongoing projects, and I think the feelings in this painting fall into that theme. For a long time, I was really against romantic love as a subject; as a teenager, I rebelled against the stereotype of the woman painter obsessed with portraying love. But recently, looking around my studio, I realized that that subject matter has kind of caught up to me, and I’ve begun to accept that a lot of my deep emotions, the feelings that often drive me to paint, are related to romantic love and that that’s totally okay. It’s necessary for me to express them in art.

It’s funny, I feel like I went through the same sort of rebellious phase with my writing: wanting to break away from such heavily stereotyped material. But now it sort of makes sense to me why romantic love is such an excessively portrayed subject for all types of artists. Because love, in all its flavors, is something that has such an ability to reach people across culture and time. I think it’s probably one of the most enduringly human things we experience.

I totally agree! Actually, I recently had a realization about my work and that was my desire to connect with people on a fundamental level through my art. It’s something I think I’ve worked for for a long time, but I only just acknowledged it consciously. I read this poem once, written by Jiuling Zhang [673-740 A.D.] in the Tang Dynasty of China about 1,300 years ago, that talked about loneliness and missing loved ones. And somehow I, a woman over 1,000 years later, understood exactly what he was saying. That’s what I want to create: something so human that it can speak through time and maybe in 1,000 years make someone feel seen, understood, and a little less lonely, like I did when I read that poem.

How do you feel you did in creating the sort of work that might touch people across time?

That’s difficult. I’d say that I have no opinion, or rather, that my opinion really doesn't matter in the most freeing way. I often feel that the pieces that come through me have their own destiny, separate from mine. So, their potential influence is completely beyond me. Time will tell.

But I have gotten to see a couple of moments where someone felt deeply through my work, so that’s one sort of success. For me, seeing art that speaks to my sadness makes me feel less lonely, but I think for some, it can invoke hurtful feelings, especially if it’s something that they don’t want to face yet. After the art show where I displayed the original paintings for The Key, I had a friend tell me that she loved all of my pieces, except those ones. They were too sad, she told me. Too depressing. Looking back on it now, after learning more of her personal love stories, and remembering how she spoke about it, I think that she didn’t like those paintings because they invoked something in her—possibly something more personal than just a general sense of sadness—that she didn’t want to feel.

It seems like most of your multi-paneled story pieces are painted quite realistically (as opposed to some of your standalone paintings that are more abstract). Is that something you do intentionally, for storytelling purposes?

I’m not sure it’s really intentional, but if I stop and think about it, I’d say in the longer, bigger stories (the ones most likely to become books) I might unconsciously work towards a balance between abstract and realism. Or at least that’s my goal, I think, that balance. There are artists I really admire who do such detailed work; every little hair is there if you look closely. I find that style fascinating, and the skill to draw realistically is important, but I currently feel zero desire to do that. I think in my own work I’m striving for a different type of wholeness. The details often come in the places that most impact the meaning of a piece, and then I try to let the rest go.

So, you tend to use details sort of like a photographer focusing their lens? The details appear in the focal point of the painting.

Yes, that sounds right to me! In The Key, the woman’s expression and the key are quite detailed, but the background is just that. It lacks the same focus and the colors there are more for the emotion of the story. Although, I can’t say that I always use details in the eye of my paintings. It really depends on the subject. Sometimes the eye is just a color or a shape and I have to figure out how to highlight that eye with the rest of the painting, with or without details. I think this makes finding that balance I mentioned earlier more of a challenge: it’s not a linear process, not details vs no details. But the challenge makes it all more interesting and exciting for me.

In this book though, the details are in the eye of the paints. I tried to focus all of the details into the expressions, but to keep the actual faces sort of undetailed, and that’s because I didn’t want to limit the story and its ability to connect to people by representing very specific faces. I wanted these figures to be part of the experience of the paintings more than the subjects of them. I also try really hard not to just paint myself, again because I want these paintings to go beyond my personal experiences, and that can be especially challenging because I sometimes use posed photos of myself as a reference in order to create believable, expressive movements and poses.

Earlier, you mentioned recent and ongoing projects exploring romantic love. Could you tell me a little about those?

I’ve been collecting love stories from my family and friends for years and I’m planning a compilation called So Called Love. I’m also part way through a collection called Sky Blue that explores the less pleasant, bittersweet feelings of love, which I find just as real as the good feelings. I think The Key would fit really well in Sky Blue and I’m considering adding it in there.